2/16 – Posted Chapter 39, which only took me two weeks. Now I’m finally into the last set of chapters with the culmination of my childhood.

2/1 – Finally posted Chapter 38, in a little shorter than my 3-week cadance. Getting there!

1/12 – Wrote and posted Chapter 37, admittedly a shorter one, in just 15 days. Just have a handful of chapters to go to finish

12/27 – Posted my latest chapter, a difficult one to write because my character was not at his best, but though long, squeezed creating it into my 3-week timeframe. Getting excited to be only a handful more chapters from being done!

12/7 – Felt great to get this very long and involved chapter, including many hours of mapping out scenes in the “Thunderball” movie, done in my 3-week cadence. Feeling like I’m seeing light at the end of the tunnel of completion of “Clubius Contained”!

11/17 – A lot of work recalling, researching and reinventing as necessary my “Cooperstown Cats” and coming up with a new alliterative name for my renamed brother character’s hockey team, but managed to stick to the three-week cadence.

10/27 – Yet another challenging chapter, including wrestling with all my old psychic wounds from the divorce, not remembering ANYTHING about this period of time (maybe I blocked it) and thus having to make it all up! Also a lot of continuity issues stringing the various scenes together against the calendar and making the details about what happened when consistent with each other, if ultimately made up! But I stuck to my 3-week cadence so I’m very happy with that.

10/6 – Another challenging chapter, covering some key psychological shrapnel from my you, but cranked out in that 3 week cadance I’ve been managing to follow lately. Yay!

9/15 – I feel good that I was able to crank out this long 30 page chapter in this 3-week cadence I am trying to stick to. 2 weeks to pound out a rough first draft, and then the 3rd week for 2nd, 3rd, etc drafts to clean, polish, and juice it up.

8/24 – Starting from scratch on this one was able to get it out in just under 3 weeks. I think I can keep to that cadence. Start with an outline then pound out a rough first draft by the end of the second week. Spend the third doing second and additional drafts as needed to clean it up, flesh it out and juice it up!

8/5 – I was able to get this chapter out in just over 2 weeks, though I did already have it outlined. This one was more about my internal thought processes after another long year of school.

7/22 – Despite being a longer chapter, tho full of dialog, I was able to get thru this one in just about 3 weeks. I’m going to try to keep to that cadence if I can. This one was more fun because it was a party with all those characters that I really enjoy writing!

6/30 – I was able to push out chapter 27 in about 3 weeks. I’d like to keep that cadence if I can!

6/8 – Chapter 26 took nearly 4 weeks as well, tho it was a longer chapter with more scenes!

5/14 – Chapter 25 took a bit longer, nearly four weeks.

4/19 – Chapter 24, which was significantly shorter, took exactly two weeks. Happy to finally be moved from Allmendinger to my last two years of elementary in Burns Park!

4/5 – Chapter 23 took 3 weeks, but it was longer and trickier, but glad it’s done and “in the can”, at least for now!

3/14 – Finished chapter 22 in 11 days. Trying to keep up with this pace!

3/3 – Finished chapter 21 in just a couple weeks, thou I had a mostly completed rough draft from before.

2/17 – Finished chapter 20 in less than 3 weeks. Excited about keeping this pace!

1/30 – Finished chapter 19 in about 3 weeks. Trying to keep that quicker pace up!

1/8 – Finished chapter 18 in under 2 weeks. Hopefully getting a little writing momentum going and on to the next!

12/26 – Finished chapter 17. Did this one in 2 1/2 weeks so keeping that momentum going in my writing!

12/8 – Finished chapter 16. Actually did it in two weeks. Spent the previous two drafting a chapter I finally decided needed to pushed forward a year in my story, from 1963 to 1964.

11/9 – Finished chapter 15.

10/10 – Finished chapter 14. Would like to speed up my writing process to get out a chapter every two weeks, but so far not!

9/6 – Finished chapter 13.

8/12 – A long haul to finish a long chapter 12.

6/30 – Finished chapter 11.

5/31 – Finished chapter 10.

5/12 – Have been having problems with my site. I’m still in the process to resolving them so folks may have intermittent access! Sorry for the confusion… I’m trying to work things out!

4/16 – Took nearly 4 weeks to do chapter 8, but it was another long chapter. Realize I haven’t been updating this for each chapter, so I should go back and do that!

3/20 – Well chapter 7 was long and it took almost 5 weeks… ugh!

2/16 – Took just 2 weeks for chapter 6, tho it WAS a shorter one. Trending well!

2/2 – Took a little more than 3 weeks to do chapter 5. I’d like to be able to stick with 3 weeks per chapter!

1/9 – Took 25 days for CC chapter 4, but had the holidays in there, but happy to keep moving forward!

12/15 – Took 23 days for chapter 3 of CC. A bit longer that chapter 2, but still less than a month. Hoping to push it down to more like 2 weeks per chapter!

11/22 – Took just 18 days to write the second chapter of CC. Will try to keep up the pace!

11/4 – Posted first chapter of “Clubius Contained”. Hoping to be able to up my writing production to get thru what should be about a 40 chapter story in 2 or 3 years!

10/14 – Now pondering on getting started on the follow up novel, “Clubius” Contained”, my narrative about my elementary school years from ages 5 to 11.

10/13 – Posted the final chapter of “Clubius Incarnate”. I had written a good chunk of it before, so it didn’t take as long to complete it. I am very pleased to have written a story from the point of view of a 3 to 5 year old, something I’m at least not aware of having been done before!

10/7 – As I work on the final chapter of “Clubius Incarnate”, I am also beginning to update my written “Two Inch Heels” introduction and chapters based on the updated version that I recorded for my podcast.

9/29 – Posted 40th chapter. Shorter than previous ones with more interior monologue than dialogue. Second to last chapter trying to wrap things up and set the stage for the next story, “Clubius Contained”, where I go to elementary school.

9/9 – Posted 39th chapter. Long and complicated, including reviewing the movie in detail.

8/3 – Posted 38th chapter. Longest one so far with a fair amount of research and crown sourcing about trip to the stadium and the events of the actual game.

6/24 – Posted 37th chapter. Quicker chapter, just took me 2 1/2 weeks.

6/7 – Posted 36th chapter. Another long one. Hope to complete this story with planned 5 more chapters!

5/3 – Posted 35th chapter. Seem to be able to put out one chapter a month.

4/7 – Posted 34th chapter. A particularly long one but with a lot of dialog.

3/10 – Posted 33rd chapter of Clubius Incarnate. Tried to capture the key movie clips and my reactions.

2/9 – Posted 32nd chapter of Clubius Incarnate. Pushing forward with another maybe eight chapters to go, tho multitasking with my Two Inch Heels podcasting.

1/21 – Posted 31st chapter of Clubius Incarnate. Closest thing I’ve written to situation comedy, but with a poignant ending!

12/9 – Finally posted chapter 30 of Clubius Incarnate, just 10 more planned chapters to go! Shooting to finish by maybe the end of April.

12/6 – Been focused on getting my podcasts of “Two Inch Heels” up on the various podcasting sites. Have an intro and first 12 chapters posted, just 41 more to go!

12/2 – Still working on chapter 30 of Clubius Incarnate, but have now posted an intro & first 10 chapters of Two Inch Heels podcast!

11/22 – Started on chapter 30 but have shifted focus for the moment to trying to publish my audio chapters of Two Inch Heels on Podbean and Apple Podcasts.

11/14 – So much for cadence! Just posted chapter 29, a very long one with several levels of story to address!

10/19 – Keeping that cadence of a new chapter every two weeks. This one, 28, built around another of my interesting developmental experiences watching TV.

10/7 – Getting into maybe a flow of posting a new chapter every two weeks! This one, 27, wasn’t part of my original outline for “Clubius Incarnate” but kind of came out of nowhere.

9/25 – This chapter 26 was rewritten based on an earlier piece I wrote about my dad.

9/15 – Got this latest chapter 25 of “Clubius Incarnate” relatively quickly and hope this momentum can grow!

9/2 – After working on or at it all summer, I finally was able to post my next “Clubius Incarnate” chapter, “Nursery School”. Turned out was very difficult to reconstruct a home-based pre-school in the late 1950s in progressive Ann Arbor, then build a whole story leading up to my one vivid memory of pleading with a kid thru the fence to get me out of there.

8/26 – Finally got my “Two Inch Heels” summary page properly updated referencing the new five opening chapters. Still in the process of renumbering all the old chapters.

8/25 – Have taken a break from “Clubius Incarnate” to try creating podcast episodes for “Two Inch Heels”, and in the process ending up rewriting the first three chapters into now five chapters. Posting the podcasts are still TBD at this point.

6/14 – Just 2 weeks to get out chapter 22 tho about half as long as the previous one, written as a recap by my character rather than scenes with dialog.

5/30 – Getting back in the groove of writing after my transition into retirement. Chapter 21 is quite long and chocked full of stuff as I start to develop that ‘tude befitting a four year old.

4/25 – Finally got chapter 20 posted, pushing the story forward up to my fourth birthday.

3/14 – These chapters of my early youth, including chapter 19 just posted seem so much harder to render, since I’m pretty much making up so much of the detail based on my few slivers of memory and what I was told.

2/14 – Another long slog with chapter 18, recreating the Christmas I spent at my grandparents house and trying to bring all my family members’ characters alive.

1/10 – I rewrote the intro paragraphs for my “Two Inch Heels” memoir to try to better capture the gist of the thing and make a more compelling case to a potential reader.

12/19 – Finally got this very challenging chapter 17 posted after sharing a draft with my aunt Pat and getting her input. This writing is much more challenging given I am writing as a very young person and obviously have no written journal to base my pieces on.

11/6 – This piece was half written back a year and a half ago when I decided to rewrite Two Inch Heels, and now I have finally gotten back to this very different “imagined memoir” from the point of view of a truly young person!

10/24 – Final chapter rewrite completed. A great deal of emotion for me to let this thing go and be what it will be, and moving on!

10/18 – Chapter 44, another quick rewrite. Almost done! Hope to have the last chapter polished off next weekend!

10/16 – Another quick rewrite of chapter 43, a climax of sorts and another one of my favorites.

10/11 – A quick rewrite of chapter 42.

10/4 – I read the new posted version of 41 and felt I needed to make more updates.

10/3 – Rewrite of chapter 41, one of my favorites.

9/27 – Rewrite of chapter 40.

9/19 – Now a particularly long chapter but sticking to my weekly pace, a rewrite of chapter 39.

9/12 – Still on a cadence of one piece a week, posted rewrite of chapter 38.

9/5 – On a role with these quicker rewrites, reworked several conversations and posted chapter 37.

8/30 – Another quick rewrite of chapter 36 despite expanding a previously summarized conversation.

8/28 – Was a quick rewrite of the 2nd half of chapter 35, since there were not summarized conversations to build out into the real thing.

8/23 – Broke chapter 35 into two parts, and posted rewrite of the first part, turning the paragraph overview of the conversation in the brewery into a major dialog scene.

8/16 – Rewrite of part 34 included truncating piece at end of initial day and turning the conversation summaries into more real conversation.

8/8 – Rewrite of part 33 took a bit more work, but some nice adds including a song lyric to keep that trend going in every chapter.

8/1 – The rewrite of part 32 was pretty quick, only adding a little dialog to replace dialog summary. It is an interesting decision when to use actual dialog vs summarizing that dialog.

7/26 – After the slog thru 30, just needed a fairly quick rewrite of part 31, again just turning some conversation summary into dialog.

7/25 – Finally posted the rewritten part 30, which I almost let remain pretty much as it was, but then decided to rewrite the summarized conversation as mostly actual dialog and did some serious expansion of the piece.

7/12 – And part 29 B quickly follows with the new title ‘Triumvirate’

7/11 – Posted separated and somewhat updated first half of 29th chapter, still with the ‘Snow Day’ title

7/10 – Posted rewritten 28th chapter, happy that these latest chapters seem to need less rework, and sorry for the length!

7/3 – Posted rewritten 27th chapter, finding a nice pacing to the piece and again some added character dialog and an additional provocative verse for “Marching to Pretoria” coming home from the village pub

6/29 – Posted rewritten 26th chapter, with just some added dialog to flesh out characters and match the continuity of more use of the Cleveland gang in my earlier Italy pieces

6/26 – Posted rewritten 25th chapter, not as extensive rewrite, just part in tunnel. Definitely won’t finish whole thing by August target, but hopefully by end of year

6/14 – Posted rewritten 24th chapter, another fairly extensive rewrite

5/29 – Posted rewritten 23rd chapter, doubling the length of the piece

5/15 – Posted second rewritten half of 22nd chapter, another extensive rewrite

4/19 – Posted first rewritten half of 22nd chapter, probably my biggest most challenging rewrite so far

3/22 – Posted rewritten 21st chapter, with significant additions of dialog

2/29 – Posted second half (part B) of now split 20th chapter, with some significant changes

2/16 – Posted first half (part A) of now split 20th chapter, because it was so long and really now lent itself to division.

2/6 – Posted the second half (part B) of old 19th chapter.

1/31 – Posted first half (part A) of now split in two 19th chapter, because it had gotten so long, including a significant rewrite adding some dialog to flesh our my characters Morgan, Jen and Sarah!

1/19 – Posted rewritten 18th chapter, with more of a rewrite adding some dialog to try and tie up Steve story better!

1/17 – Posted rewritten 17th chapter, with a minor rewrite!

1/13 – Posted rewritten 16th chapter, with very little I felt I could rewrite this time!

1/12 – Posted rewritten 15th chapter, with lesser rewrite!

1/4 – Posted rewritten 14th chapter, with lesser rewrite!

12/26 – Posted rewritten 13th chapter, with big rewrite of a major scene!

12/15 – Posted rewritten 12th chapter, a long piece!

12/8 – Posted rewritten 11th chapter, trying to capture a very different feel of things in Spain!

11/22 – Posted rewritten 10th chapter, I really liked how I was able to amp up characters and get a good flow!

11/9 – Posted rewritten 9th chapter

10/20 – Posted rewritten 8th chapter

10/19 – Posted rewritten 7th chapter

10/9 – Posted rewritten 6th chapter

9/29 – Posted rewritten 5th chapter

9/22 – Posted rewritten 4th chapter

9/8 – Posted rewritten 3rd chapter. Feeling good about rewrite enriching depth of story.

9/2 – Posted rewritten 2nd chapter with significant rewrite involving adding some key conversations

8/18 – Posted a now rewritten, expanded and divided 1st chapter of my memoir, now titled “Two Inch Heels”, of backpacking thru Europe in 1973 at age 18.

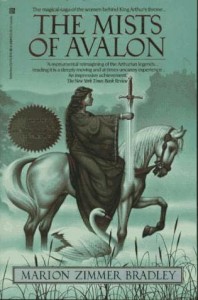

At my suggestion, our daughter Emma at age 14 read Marian Zimmer Bradley’s epic feminist reframing of the oft-told Arthurian legend and was profoundly affected and inspired by its story, scope, and deeply drawn heroic but flawed characters. It was a much more sophisticated tale than most, because it was not about good and evil (with characters falling obviously into one of those two categories), but rather a story where a number of compelling characters wrestled with doing their duty and following their heart in a highly challenging transitional and high-stakes context.

At my suggestion, our daughter Emma at age 14 read Marian Zimmer Bradley’s epic feminist reframing of the oft-told Arthurian legend and was profoundly affected and inspired by its story, scope, and deeply drawn heroic but flawed characters. It was a much more sophisticated tale than most, because it was not about good and evil (with characters falling obviously into one of those two categories), but rather a story where a number of compelling characters wrestled with doing their duty and following their heart in a highly challenging transitional and high-stakes context.