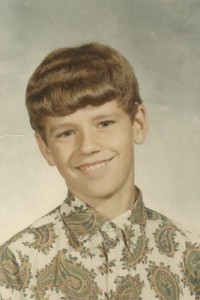

Oh say can you see

My eyes if you can

Then my hair’s too short

The iconic Woodstock music festival, which I knew nothing about at the time, was happening in upstate New York that August, the climactic event in what some would later call the “summer of love”. But the musical Hair at least made me familiar with that counterculture that was emerging with its “flower children” driven by a mantra of “peace, love, joy” facilitated by “sex, drugs and rock-n-roll” which allowed you to “tune in, turn on and drop out”.

I was secretly a wannabe hippie/revolutionary myself, inspired mostly at this point in my life by the compelling popular culture of the time. Listening to the transcending the ghetto songs of Motown artists like The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson and many others. Or the activist counterculture fervor of many of the white folk-rock artists of the late 1960s including The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, Stephen Stills, and Bob Dylan. Reading comic books about super-powered anti-heros fighting for the soul of society like Batman, The Flash, Spiderman, and Dr. Strange. Reading sci-fi classics like Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series each about a different sort of passionate, transformational, outside-the-box, bigger than life character, from the nihilistic anti-war submariner Captain Nemo to the visionary psycho-historian Hari Seldon.

You would never know it to encounter me – a shy kid with short hair and conventional clothing – but I harbored a megalomaniacal streak and delusions of grandeur, fantasizing that I would somehow someday help lead the revolution that would transform society. At this point that was all mostly repressed and I didn’t even dare “let my freak flag fly”, speak a contrary word to anyone, let my hair grow or wear flared pants (now coming into popular fashion), let alone the iconic bell-bottomed hippie gear.

From this wannabe so much more than a meaningless kid orientation, junior high had taken its toll. I had entered the institution three years earlier thinking myself somehow special – smart, an advanced student, shy but capable, and a leader able to navigate the social milieu of my classmates and other peers. But for me at least it had not been so much about exploring your potential as just somehow surviving going through puberty jammed in with so many other kids that same awkward age. A child of divorce lacking self-esteem, each day felt like an unrelenting pressure cooker of comparing myself (mostly unfavorably) to my peers and not having a thick enough skin to suffer their own negative feelings projected on me. Witnessing the teasing and bullying daily around me, I developed a great fear of being singled out in any way and thus subject to teasing and ridicule, so I had learned to play it safe by being as unremarkable and average as possible.

The extreme stress of trying to implement this strategy day after day had led me to both a weakened immune system leading to regular illnesses, plus the willingness to feign additional illnesses when I simply did not want to face school on a given day (sometimes extending to a week or more). Add to this an injury I sustained in May of 1968 getting my ankle chewed up by the flywheel of a “minibike” (a tiny motorcycle popular at the time that one of my neighborhood friends had) that left me in a cast and crutches for the last six weeks of school. It was a perfect excuse to stay home for that entire period. All told I probably stayed home a full quarter of the days I should have been in Junior High.

Though we seldom talked about my school avoidance as such, my mom seemed to implicitly accept or at least not challenge my coping strategy, given that one of her parenting mantras had always been that “bright kids will tell you what they need”. But also at the time she was going thru a very stressful period of her own, having divorced four years earlier and continuing to go thru an extended depression, while as a now single parent trying to maintain a household and raise two boys, myself and my three-year-younger brother Peter, himself wrestling with obesity since his early childhood.

But earlier in this current year, my mom had finally tried to at least confront the problem, arranging a meeting of her and I with my school counselor to negotiate my return to school after several weeks missed due to illnesses, real and concocted. I recall in the meeting being uncomfortable sharing how I felt with either my mom or the school counselor, seeing them both as iconic authority figures whose thoughts on the matter were way more significant than my own. The end result of course was I did go back and finished my time in junior high with okay grades, mostly “B”s. When I finally finished school in June, like every year when the last bell of the last day of class came, I felt a great sense of relief and profound liberation, more so this time round because I knew I would not be going back.

That past spring I had also been exposed to the world of politics, when my mom, who had previously taken on the role of precinct chair for the local Democratic Party, played a part in the successful mayoral campaign of our neighbor, Robert Harris, elected in April of 1969. I remember my mom hosting cocktail parties to raise money and garner support for Harris from her large circle of friends in the community. She also recruited me to do canvassing calls to people in our precinct to identify voters likely to vote Democrat so she could make sure to get them to the polls on election day. And on that day, had sent me out on my bicycle with a list of people whose doors I needed to knock on and remind to vote. It was perhaps the first opportunity I had had in my life to make at least a small contribution to something in the “real” adult world, something I noted and salted away for later.

The summer had been full of self-initiated activities as summers always had been for me. I played my last year of Little League baseball and enjoyed following the major leagues as well, particularly the Detroit Tigers, their ballpark just some 40 miles east of Ann Arbor. I even had several opportunities to go to games with my Little League team or with my friends’ parents. Some of the time I would hang out in Burns Park just across the street from my house with my neighborhood friends or I would spend time at their houses. But I was mostly a kid into what would be considered “nerdier” hobbies.

Baseball being of great interest to me at the time, for my birthday in April my mom had gotten me the “BLM” (Big League Manager) baseball game, where you could play the real major league teams against each other based on each player’s batting and pitching statistics from the previous season. The previous season had been 1968 when the Tigers had won 100 games and had gone on to beat the St. Louis Cardinals in a seven game World Series. I taught my brother Peter how to play BLM and together we played the entire month of April schedule for all ten American League teams, a total of some 130 games, each one taking about an hour to play. We both knew the ins and outs of the game and provided the “color commentary” for each game and became intimately familiar with all of the league’s players and their particular abilities. We of course kept box scores for each game played and batting and pitching statistics for all the players.

I also had a couple neighborhood friends that were into the Avalon Hill historical military simulation games that I liked to play. My favorites that summer were Battle of the Bulge, the last-ditch offensive by the Germans through the mountains of the Ardennes in 1944, and Midway, simulating the climatic 1942 naval battle of World War II in the Pacific. When my friends weren’t available to play I would set Battle of the Bulge up in my room and play it solitaire, or not actually play through the game but just endlessly obsess over the best possible initial setup for the American army units to stop the German onslaught.

These games, whether baseball or warfare, were all about systems and strategy and simulations based on statistical probabilities with the introduction of some realistic randomness based on the role of dice (or in the case of BLM baseball, spinning a spinner with 1 to 100). With my active imagination I could fantasize I was right there in the dugout managing my team or in headquarters staring at the maps of the theater of operations, ordering my military units to move, attack or hold fast. It was the part of my life where I felt the most fully engaged, where it did not matter I was just some random kid in the real world.

But now it was Labor Day with school about to start again. I was filled with the usual anticipatory dread and sense of resignation at returning to the routine of school, though this time at least I knew I would not be returning to the Tappan pressure cooker. My parents were both adventurers of sorts, and I had learned from them that life at its best was an adventure, and now finally going to high school would be one for me. I felt this optimism because I had encountered some high school kids on various occasions and had noticed and noted how they seemed to be so much more grown up than I was. Guys with facial hair and young women with ample breasts and figures, more daring hippie-ish clothing being worn by both genders. I longed to be more like that, more like a real “I am what I am” fully realized person, than an intimidated undifferentiated kid.

Click here to see the next installment, “Part 2 – My First Year”.